Modeling Inclusive Practice in Denmark

How do we make the classroom work for all students… and for adult learners too?

In fall 2024 I had the great privilege of exploring that question with educators across Denmark. I facilitated workshops in Aalborg, Aarhus, and Copenhagen, working with groups of teachers, school leaders, coaches, and university faculty.

In eight workshops over two weeks, we explored how to do school differently.

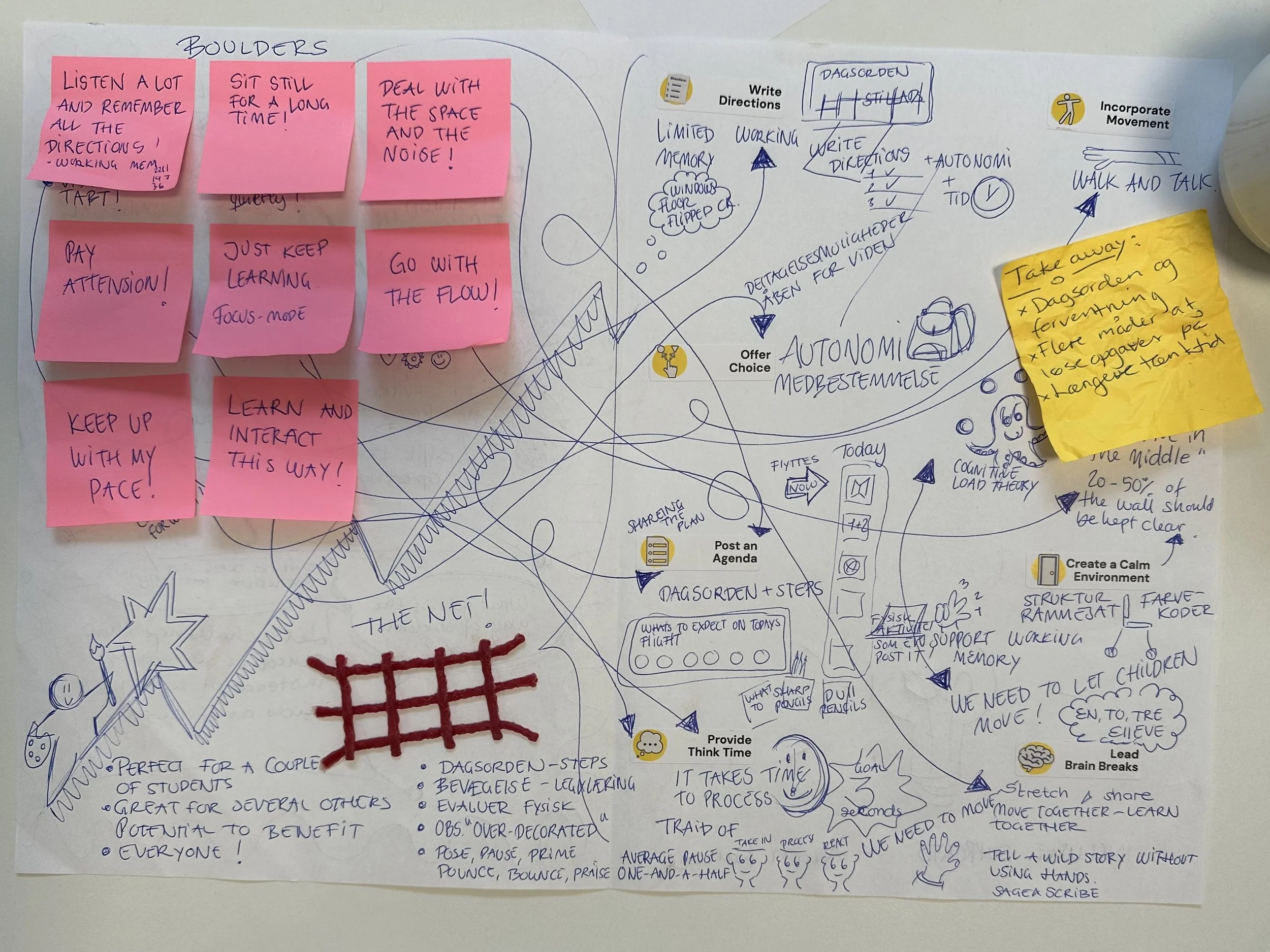

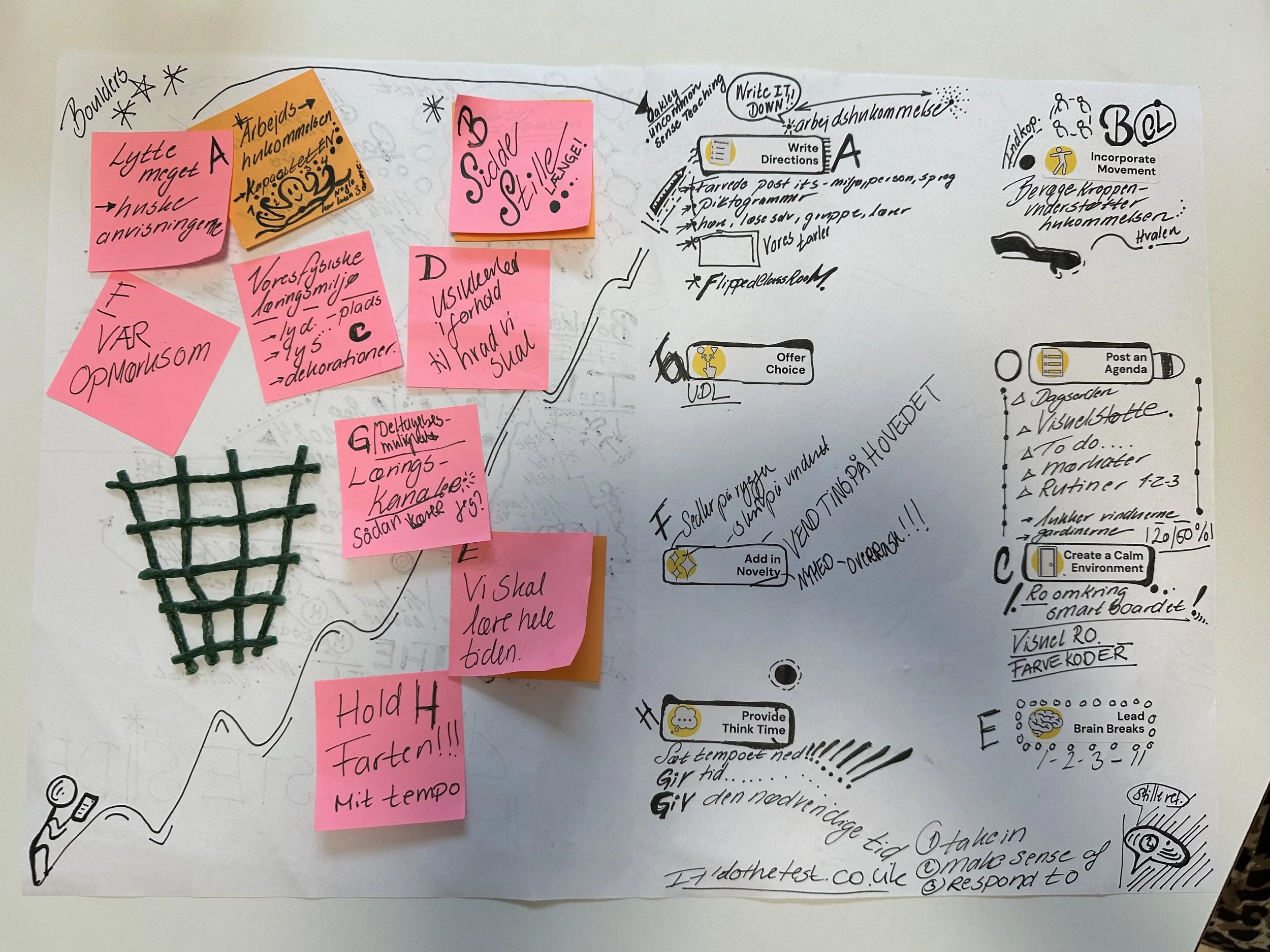

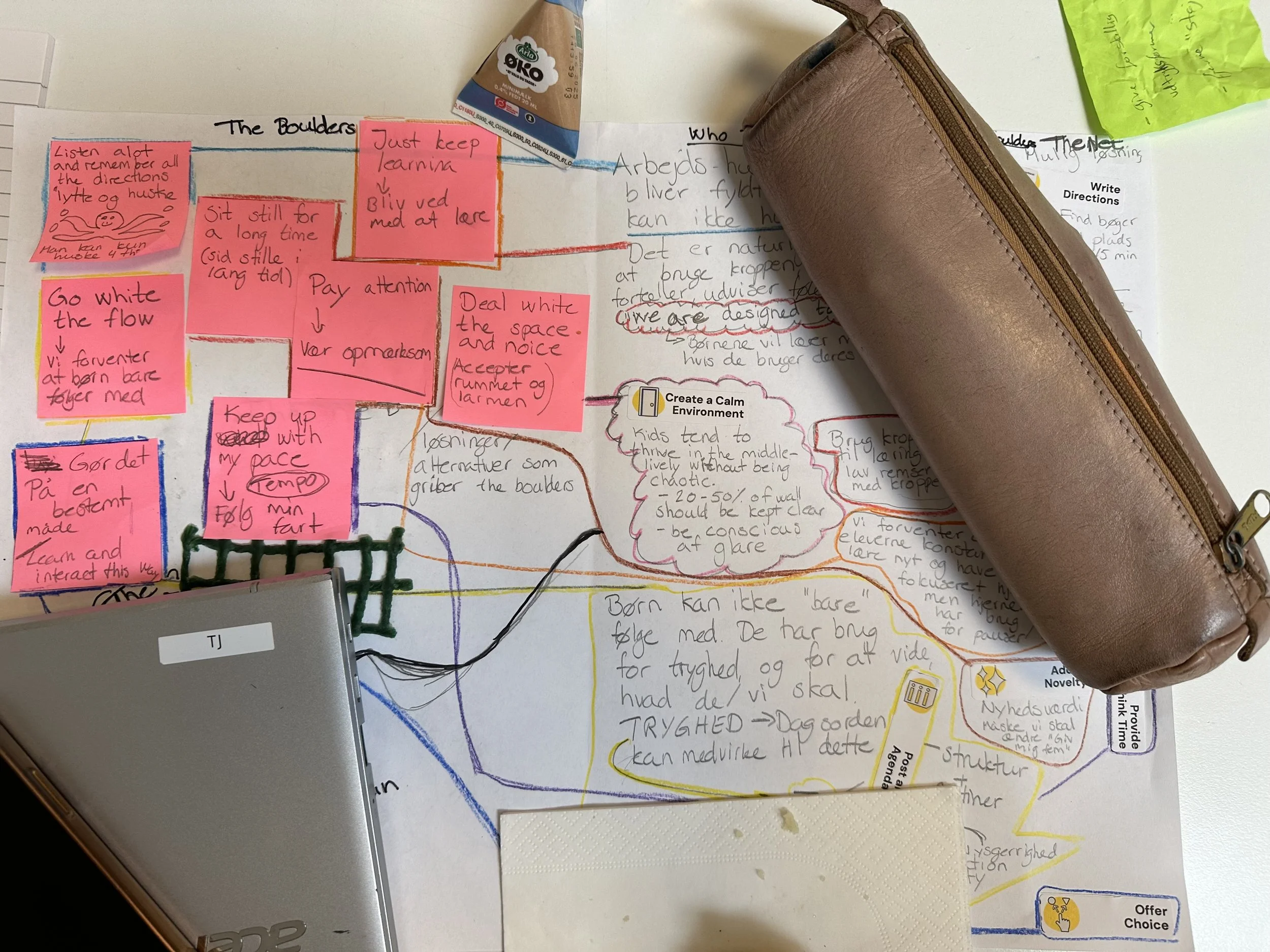

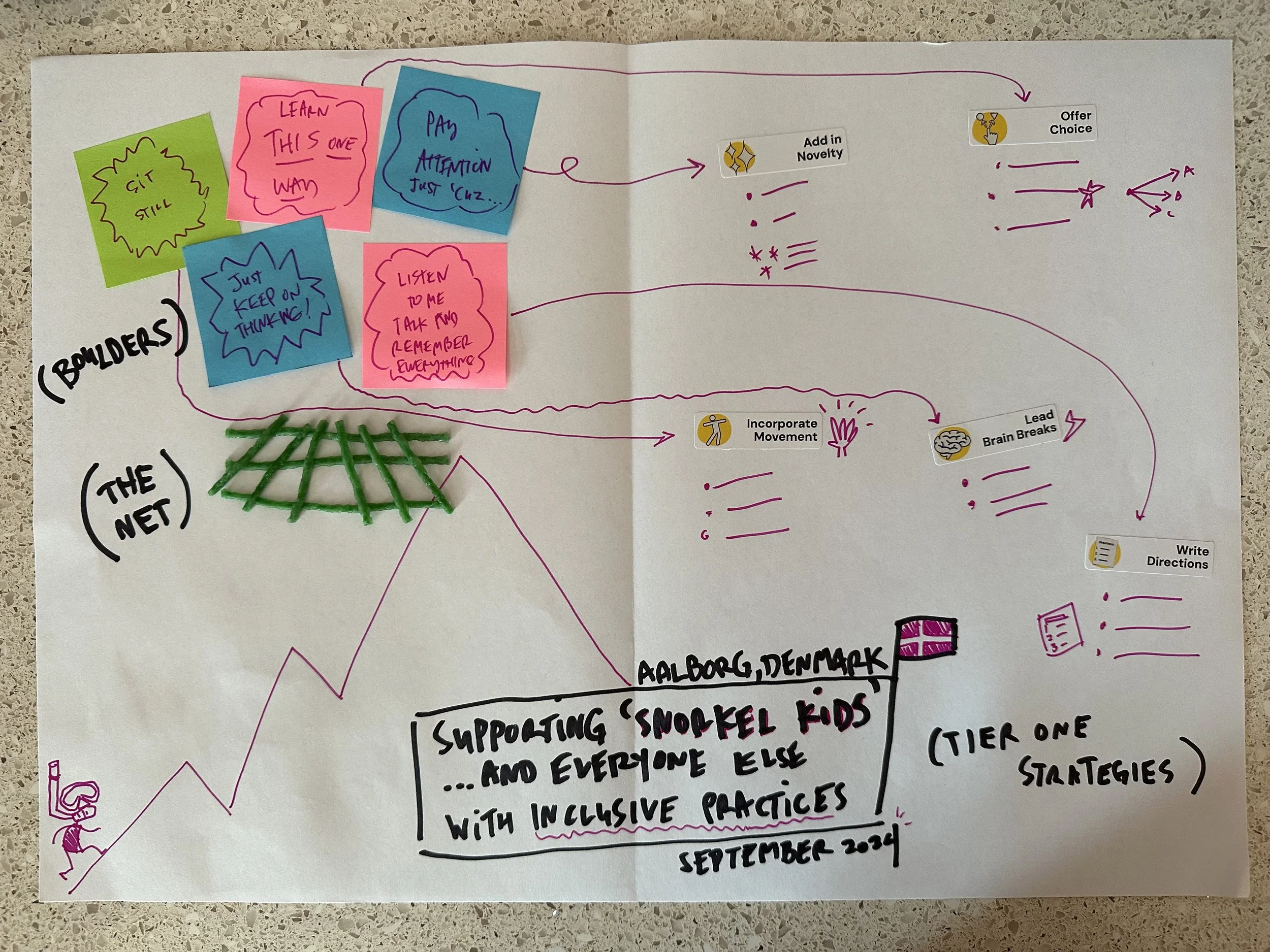

We examined the unnecessary boulders we through in kids’ paths on their trek up the mountain of learning. And we looked at low-lift practices we can use to minimize their impact.

Here are some of the themes that we explored in our investigation of inclusive education—and how these basic principles of learning apply to professional learning for adults, too.

Oops, We Designed School Wrong…

John Medina wrote in Brain Rules:

“If you wanted to create an education environment that was directly opposed to what the brain was good at doing, you probably would design something like a classroom.”

Learning is hard. And it should be! We learn best when we are reasonably challenged.

But the way we “do school” makes learning harder than it has to be. We expect kids to sit still, listen for long stretches of time, and just go with the flow—none of which is necessary for learning. But they are essential for “doing school.”

Fortunately, educators have the power—and the responsibility—to use practices that minimize the impact of these unnecessary boulders. Think of it as building a net that catches the boulders before they come crashing down on that mountain of learning. The net is made up of some basic, whole-class inclusive strategies. And like good inclusive practices:

In our workshops we explored many of these inclusive practices. Participants examined why these practices matter to students, and experienced how they even support adult learners.

Here are four of these practices.

Write it Down

Written directions might be both the unsexiest and most important inclusive practice.

Schools often expect learners to just listen and remember everything. Educators talk at students a lot, and the expectation is that they hear, understand, and retain everything that is said.

That’s an unnecessary boulder. Solely giving verbal directions overloads learners’ working memory. That drains neural resources that they could otherwise use for learning… and leads to frustration and overwhelm.

Write down the directions.

Any time there is a task or activity that individuals or groups will do over time, write down the steps. This helps all learners—not just those with attentional differences, but those who were distracted, stepped out of the room for a minute, or just need a reminder.

I made an effort to post clear directions for every activity, letting participants focusing on the discussion itself.

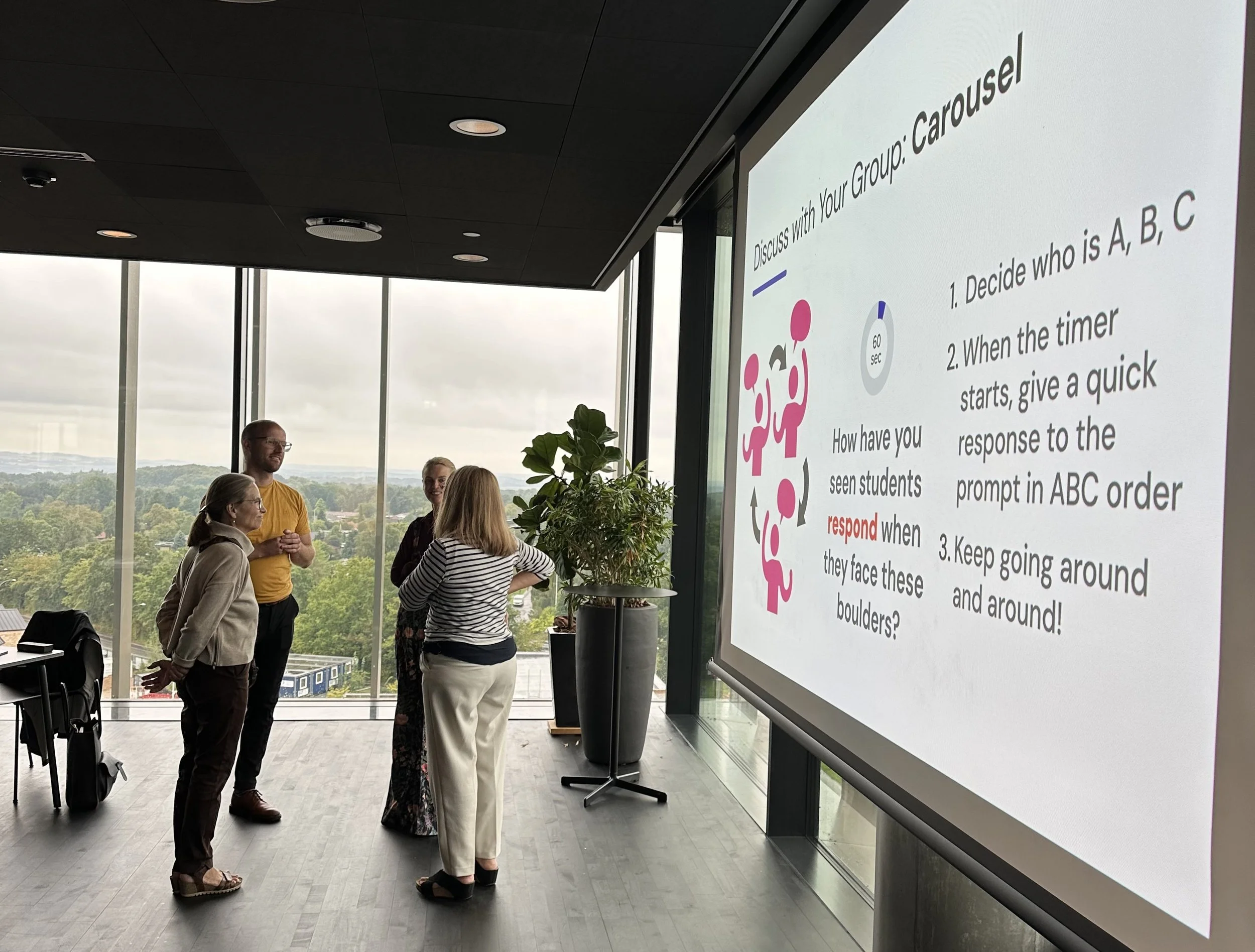

During Carousel, an activity that was new to workshop participants, the steps, timing, and prompt were all displayed as reference.

In your classrooms, try making a template any time you’re asking students to do a multi-step task over a period of time. Try this one for starters.

Written directions: simple but powerful.

Mix it Up

Our attentional system is complex. But one thing we know about attention is that it is drawn to things that are out of the ordinary.

Expecting learners to just pay attention just because we say so is yet another boulder that need not be part of how learners learn.

Add in novelty.

This is just one way to guide attention, but novelty can go a long way to capture student attention and direct it where we want it.

Instead of handing out a copy of the workshop slides, in our workshops I guided participants to construct the “mountain of learning.” They used post-it notes for the boulders and Wikki Stix to build the net of supports. Check them out!

In your classrooms, try out mixing things up with novelty that grabs students’ attention and makes them perk up and wonder…

Walk in to school one day wearing a funny hat that has to do with a character from a novel

Ask questions that are a little out of the ordinary

This great Edutopia article from Phillip Done has some terrific ideas.

This doesn’t mean that every day is a free-for-all. Structure and predictability are still key.

But let’s try to be aware of when routines become ruts, and add a little spark of novelty.

Get ‘em Moving

Our bodies are designed to move. And they will find a way! Who has a foot tapper or pen twirler in their classroom? Or which of you is a gum-chewer, or a doodler?

Requiring learners to sit for long stretches of time is an another unnecessary boulder that interferes with learning. Being still does not lead to learning; it gets in the way. A particularly cheeky first-grader I once heard of captured this bluntly, but beautifully: When his teacher told him to stop wiggling around in his spot on the rug, he told her clearly,

“Lady, I can sit still or I can listen. Pick one.”

Incorporate movement.

Get learners up and get their blood pumping. This can help all our learners with regulation needs, and it can also help those sleepy-eyed folks too.

We moved a lot in our workshops. We did some rounds of Stretch & Share to help participants move their bodies while sharing out with their tables.

In your classrooms, there are lots of ways to get students moving. Ensure you have a clear structure for the activity, share clear expectations, and model and practice.

For getting kids in groups to brainstorm multiple answers to a question, try out The Carousel

Of course, we need to be mindful of folks with mobility needs that might conflict with our expectations for movement, and design activities accordingly.

Why sit still when movement boosts learning?

Let ‘em Decide

When teachers plan lessons, we tend to imagine every student doing the one task we have planned. It’s almost as if each step of our lesson plan starts with “all of the students will…” fill out this worksheet, write an essay, etc…

But insisting that every learner participates and engages in the one way that we have decided is yet another boulder that is not essential for true learning.

Offer choice.

Giving options to learners is the best way to combat that “learn just this one way” boulder.

The choice is powerful: rather than giving one prompt or image to respond to, folks get to decide which is most meaningful to them. They will likely have more to share, and their group members may hear something they wouldn’t have thought of otherwise.

And remember that constructed mountain activity? No one was required to do it. I posed the choice to take traditional notes on paper or on a device, or to construct the mountain, or to maybe sketch their notes.

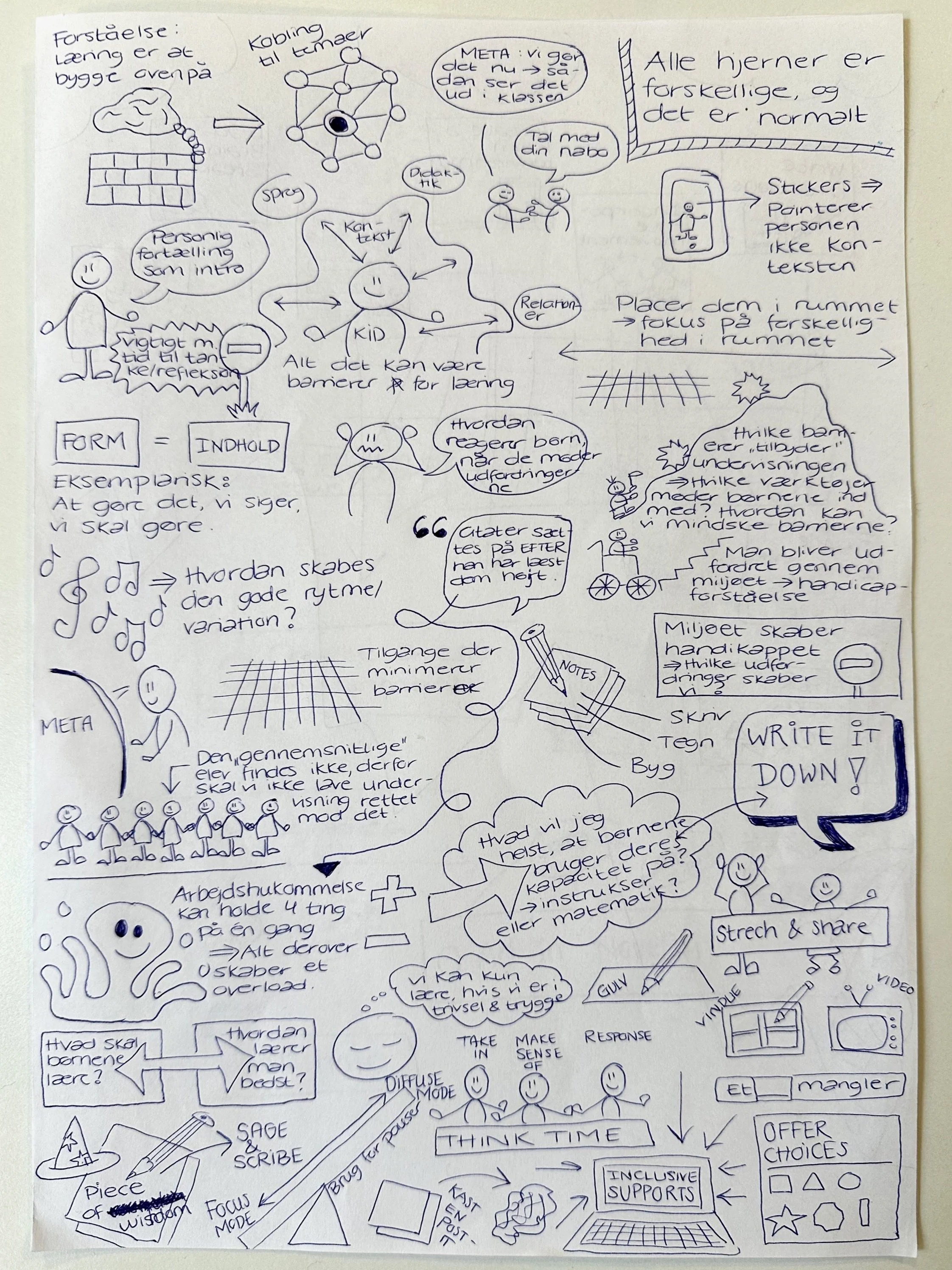

One participant chose to draw, and they produced this beautiful and helpful reference.

In your classroom, try some starting points for offering choice:

choice in how kids express themselves: words, image, gesture

a choice of quotes or prompts to respond to

choice in homework: even or odd problems; pick two of three short stories

Read more about simple ways to offer choice in my blog post, ”Fries or Salad".

Let them choose. Choice builds engagement and learner autonomy.

There were many opportunities to make choices in our workshops.

With a group of coaches, we used Say Anything to review concepts from the day before.

In this activity, folks see four images from concepts we’ve already explored, numbered 1–4. They choose one, hold up the finger that matches their choice, and say… anything about that image to their group.

Inclusive Practices for Learners of All Ages

All across Denmark educators are grappling with how to do school differently—so that students feel seen and valued, and are able to learn. I’m grateful to have been invited to help folks think about the mindset we need to have about doing school differently, and to share some methodology that helps to make this real for kids… and adults too!

Join me in rethinking school together—for students, and for us all.

I owe a great thanks to educators and organizations across Denmark for inviting me.

Mette, Henrik, Katrine, Cathrine, Charlotte, Dorthe, Mathilde with Den Mangfoldige Folkeskole and UCN

Peter, Marie, and Louise from Dafolo

Sannie, Christian, Ebsen, Michael and Jakob from Katrinebjergskolen

Mette, Anna, Mette, and Mette from Aarhus PPR

Tak! 🇩🇰